If ringing someone is the final lifeline for help, AT&T’s Randall Stephenson appears to be making his last call. The telecom company’s chief executive has launched an $85 billion bid to buy Game of Thrones producer Time Warner.

It’s easy to see why Stephenson would reach for a transformative deal. His main business is shrinking in a highly competitive industry. He built his legacy as a telecom executive, and while he took steps to consolidate AT&T’s strength, his management has produced substandard returns.

Stephenson may have the right intentions, hoping he will lead the sector in consolidating supplier with product, so-called vertical integration. But scratch the surface of the deal’s strategic and financial logic, and it falls apart. It rings instead of managerial capitalism, a risky mindset whereby lead executives use shareholder money to move their company outside core strengths, betting instead on their own talent and versatility.

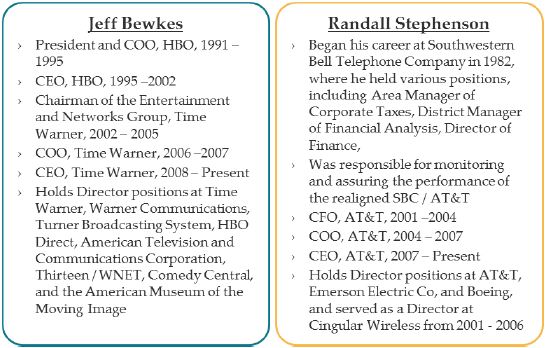

Stephenson has deep experience in telecoms. He began his career in the finance department of Southwestern Bell Telephone Company. He spent nearly 35 years shaping the company’s spot in the telecom business. As the company went on a quest to partially reconstitute the AT&T of old telephone dominance, he began his steady ascent through the ranks, overseeing Corporate Taxes, Financial Analysis and ultimately Finance. Ten years ago, he oversaw then SBC Communication’s acquisition of Bell South. He was then rewarded with the CEO position in the newly renamed AT&T in April 2007.

AT&T still is in part an old-fashioned telephone company managing communications “pipes”, the infrastructure that pushes voice and data to customers. It contributed about 13% of the company’s overall revenue in the first nine months of the year, but fell nearly 13%, digging a deeper hole from the prior two years.

Newer parts of AT&T’s business are challenged as well. Revenue in the consumer mobility segment – the group that sells cellphone plans to Average Joe – fell nearly 5% in 2015 and didn’t grow much the year earlier. Other segments, like its largest “business solutions” segment that sells internet, traditional phone, and cell services to companies, are similarly stagnant.

It’s hard to pin it all on Stephenson. The pipes business is subject to forces of commodification. Scale helps, but just as AT&T was beefing up businesses that fit its strengths – like adding DIRECTV and investing in wireless – consumers’ habits changed. Companies that deliver content still chase how people want to receive it. All managers, not just Stephenson, fight price pressures to optimize costs.

Still, AT&T’s stock price fell 8% since Stephenson moved into the corner office roughly ten years ago. During that same period, the S&P 500 rose by 42% while AT&T’s competitor Verizon has risen by 20%. AT&T shareholders have only the dividend to show for their ownership over this time, and even then AT&T underperformed both Verizon and the S&P 500 on a total return basis.

Small wonder Stephenson is under pressure to do something transformative. That’s where AT&T’s fastest growing business, the “Entertainment” segment, comes in. This group includes video-on-demand and was bolstered by the company’s acquisition of DIRECTV in 2015.

At first glance, AT&T’s deal appears to be following the playbook of a less-conventional merger category called “vertical integration”, the concept that owning the supply chain is enhanced by being with the product, partly because it gives the supplier visibility into consumers’ interests. AT&T hopes to use data to target a content push. With both the outlet and the show, AT&T plans to control pricing and delivery.

But the deal appears to fall short simply because the fundamental rule of mergers – that one plus one equals more than two – doesn’t hold up. Time Warner might find it is more difficult to work closely with other pipes companies like Verizon, for example, under AT&T ownership. It is also unclear how this acquisition helps AT&T address its core business challenge today: improving revenue from mobile and internet subscriptions. For example, if AT&T limits access to HBO to subscribers who use AT&T, this could hurt HBO more than it benefits AT&T.

The numbers don’t add up either, as AT&T is paying a hefty price. The revenue synergies will increase earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization by just $400 million by 2019, less than 1% of the company’s total. This calculation assumes an aggressive margin of 40%, well above both companies’ current margins, giving AT&T credit for cost synergies it hasn’t specified. Assuming a multiple of 10 times this number, another aggressive assumption relative to the current trading values, it will add $4 billion of value to the combined company, well below the premium of over $20 billion Time Warner is paying to buy AT&T.

If the two don’t belong together, it becomes a deal less about integration and more about transformation, which implies that Stephenson believes he is better at overhauling an industry than managing the one in which he’s spent a lifetime. Managerial capitalism is risky under any circumstance, and more so when shareholders are more passive. In this sense, AT&T is at high risk. The top three AT&T holders are passive index funds owning more than 14% of the company’s shares. Only one of AT&T’s top ten shareholders has a stomach for challenging management.

Stephenson can point to one important example of managerial capitalism that could give shareholders hope. In 1995, Michael Jordan, CEO of 109-year old electricity company Westinghouse, faced strong industry headwinds and a declining business. Jordan decided to transform the power company into a media company, buying CBS, Infinity Radio, and other assets over a few years. In 1997, the company shed all legacy Westinghouse assets and became strictly a media company, changing its name to CBS.

Westinghouse’s deal ultimately also delivered real value to shareholders– shares increased nearly three-fold through 1999 when Viacom bought CBS. But Westinghouse had several key differences, including, importantly, that its deal to buy Infinity brought radio expert Mel Karmazin on board. Karmazin used inside knowledge to help boost CBS over those years. He is credited with much of the company’s success. By contrast, Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes plans to leave after a short transition period.

For now, shares of the company are trading as if the deal may not close. This in part may be a result of concerns the deal will be met by regulatory and political headwinds, including that President-elect Donald Trump said the deal was an “example of the power struggle” he is trying to fight. But shareholders should consider questioning the deal’s merits too.

Stephenson’s quest to become a media company CEO uses other people’s money to cement his own legacy as something other than a telephone executive.