Mature no-growth companies can beat returns of fast growing innovators by operating efficiently and smartly acquiring other mature no-growth businesses (see Redefining Value in Tech). There are also examples of executives dangerously overreaching to transform their companies by overpaying for a company when growth in their business starts to slow (see Saved by the Bell?).

But companies can justify paying a large premium for a faster growing company if the potential synergies created by the merger outweigh the premium they are paying. These deals often hinge on the ability of a company to achieve revenue synergies – which is often harder to estimate, causing shareholders to scrutinize them at the outset of a deal. However if analyzed accurately, deals that produce revenue synergies can be a boon for valuation. The 2002 merger of eBay and PayPal (recently public again after being spun-off by eBay) is a perfect example.

The foundation for justifying any acquisition starts with a simple premise: the financial benefits of the transaction to be realized over time need to outweigh the upfront premium. Specifically, an acquirer must be able to generate incremental earnings as a combined company, which is commonly referred to as “synergies,” by achieving greater sales than the companies can on their own or by saving on costs through economies of scale, among other things. If the company can generate faster revenue growth on a sustained basis as a result of the transaction, it will often benefit from multiple expansion too.

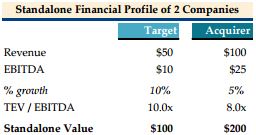

The following hypothetical example provides a framework for evaluating whether the strategic rationale for a combination justifies the price. Let’s assume a company wants to acquire another company that is half its size but has revenue growing twice as fast, as shown in the table to the below.

The target demands a 50% premium, which is significant compared to the typical 25% to 30% premium most acquirers pay on average. In this example, the acquiring company needs to create at least $50 of additional value for the transaction to be worthwhile to shareholders.

Part of that value will come from synergies, and specifically in this case revenue synergies, given the acquirer is interested in the seller in part to access its growth. (Cost synergies have been omitted from this example for simplicity.)

In this example, half of the target’s customers overlap with the acquirer’s customers. If the acquirer is able to sell its products to 25% of the target’s nonoverlapping customers and sell the target’s products to 25% of its non-overlapping customers, it will generate $25 of incremental revenue. Given the assumed margin of 25%, it will add approximately $6 to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). On a blended multiple, $55 in value is added, slightly more than the premium.

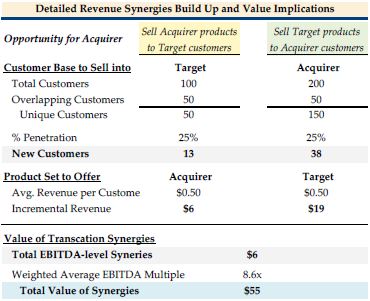

The eBay/ PayPal merger succeeded in part because it created revenue synergies by attracting new customers to the platform and increasing the ease of its use through PayPal. By increasing the number of transactions, both PayPal and eBay bolstered their revenue far more than analysts projected for each company before the transaction, as the charts below show.

These charts, of course, are backward-looking, and it isn’t guaranteed the buyer will achieve these synergies at the outset of a deal. It is harder to estimate the success rate in cross-selling the acquirer’s products to the target’s customers than the cost savings from eliminating redundant positions or closing the target’s corporate headquarters, for example. This is why acquirers often will not get full credit for revenue synergies from shareholders and creditors until they have been achieved.

As a result, corporate managers and their advisors need to carefully evaluate synergies. They can justify a deal certainly, but only if reasonable assumptions are made.

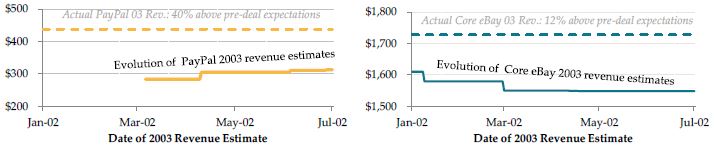

If revenue synergies do come to fruition, as they did with eBay, companies can often benefit from a second deal characteristic: multiple expansion. Once a company shows the growth of the two companies together is greater than it was alone, the market also often rewards the new company with a higher trading multiple.

For example, eBay’s multiple expanded as time went on, as shown on the chart below. In the three months leading up to the acquisition, eBay’s average “next twelve months” revenue growth expectation was 44% and its average revenue multiple was 11.9x. After the transaction closed and the companies were integrated, eBay’s 6-month average growth was over 60% and its 6-month average revenue multiple increased to 13.0x.

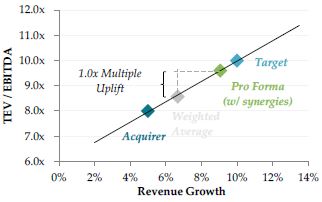

The hypothetical chart to the below shows how another company might benefit similarly by multiple expansion if a merger creates additional revenue growth. The chart is oversimplified, because growth and multiples don’t have a perfectly linear relationship. But they do have an upward-trending one. The chart shows how a company moves up the line simply by achieving higher revenue growth. In this example, the weighted average revenue growth rate of the merged company, not including synergies, was roughly 7%. But the company is able to grow revenue 9% after the merger. As a result, its multiple increased. As demonstrated in Redefining Value in Tech, a change in a firm’s long-term growth rate increases its overall value using a discounted cash flow methodology, which consequently increases the implied valuation multiple. This two-fold benefit to a company is reflected in the value.

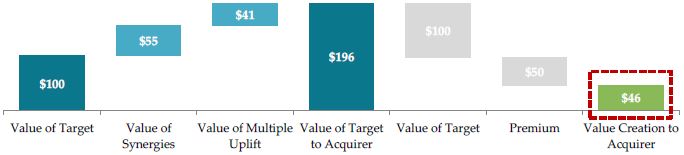

Let’s apply this dynamic to the hypothetical example as shown in the chart below. A company might squeeze $55 of value out of the combined company because of revenue synergies. It could realize another $41 of value because it will also trade on a higher multiple (1.0x the $35 of combined EBITDA plus another $6 in value as a result of the increased EBITDA due to revenue synergies) after the deal, creating an additional $46 to the merger on top of the premium.

Acquirer’s shareholders are taking a risk when a deal is announced that the company will be able to achieve the incremental revenue growth projected by management at the time of the announcement. Management teams and their advisors are often overly optimistic in projecting revenue synergies, so the rationale of mergers should be carefully scrutinized before taking growth assumptions at face value. However as a management team continues to demonstrate that revenue synergies are being realized, both the growth and the multiple expansion will continue, making the deal a perpetual windfall for valuation.