Rarely does an old fox have an opportunity to learn from the mistakes of a young wolf. But Elon Musk’s effort to merge his companies SolarCity and Tesla offers an important lesson for media mogul Sumner Redstone if he attempts to merge Viacom and CBS. Musk’s effort, announced over the summer and being voted on next month, has made several shareholders howl. While Musk wasn’t a part of the negotiations, he stands to financially benefit to a degree other shareholders do not.

We take no view on the strategic merit of these deals; nor do we suggest they should not be completed. Rather we think that Musk – and Redstone, if he eventually attempts something similar – might have an easier time bringing all shareholders on board if they fully disclose how their economic exposure to a deal is different from other shareholders, and potentially offer remedies for that difference.

In the Musk deal, Tesla is buying SolarCity. More than a half dozen shareholders have reportedly filed lawsuits, including one by the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, the Boston Retirement System, and the Oklahoma Firefighters Pension and Retirement System, among others. (Tesla has said the lawsuits are without merit.)

Several other Tesla shareholders, including Fidelity, are said to back the deal, and on the face of it, it’s easy to see why. Tesla and SolarCity shareholders have already bought into Musk’s genius and industry visions, and he believes in the combination. Moreover, there is a very encouraging headline that Musk “owns roughly 20% of both companies.” Why not go along with the pack, let the mastermind bring together his pups, and nurture them to the next level of dominance? He wouldn’t allow Tesla to overpay for SolarCity or SolarCity to sell on the cheap, right?

The dynamic isn’t quite that simple. Musk’s actual stakes are 21.9% and 18.4%, respectively in SolarCity and Tesla. Overlapping ownership in mergers makes Musk’s incentives– and Redstone’s – different from the interests of non-overlapping shareholders. It is the case even if the percentage ownership stakes are identical in both companies, but it is exacerbated if the stakes differ.

In a merger, the issue of overlapping shareholding manifests itself in the payment of premiums. At the outset of a deal, a buyer offers the seller more than its current value. If all goes well, the buyer eventually benefits from future growth the seller forgoes. In the beginning, this amounts to a transfer of value from the buyer to the seller.

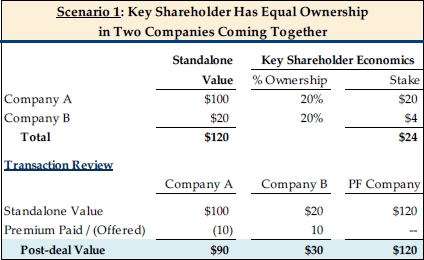

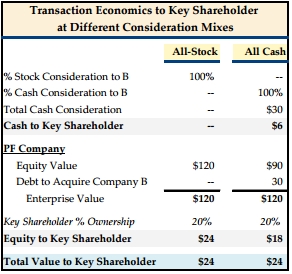

When a deal has overlapping shareholders, this value equation changes. A walk through the math first shows how deal premiums typically work when a shareholder owns a stake in both the buyer and the seller. Company A is worth $100, and it is buying Company B worth $20. Company A pays a $10 premium, and to simplify the example shown in chart “Scenario 1,” the combined company has no synergies. The premium reflects the idea that Company A believes the combination will be worth more than $130 someday. But for now it’s worth the sum of the two before the deal: $120.

Upon announcement, Company A’s shareholders transfer some of their own value to Company B, the idea behind paying a premium and taking the risk for the potential return in the future. As a result, Company A is worth $90. Company B is worth $30. (Public share prices of targets and acquirers often reflect this dynamic upon announcement. Stocks of the acquiring company may fall, or if synergies are present, rise less than the shares of the seller.)

If a shareholder owns only Company A, he has lost 10% of his value as a result of the deal. If he owns Company B only, he’s gained a half. But if he – call him Shareholder Alpha – owns 20% of both companies, he breaks even. The combined stake was worth $24 beforehand – $20 from Company A and $4 from Company B. It is worth $24 after the deal as well – $18 from Company A and $6 from Company B.

On the face of it, Shareholder Alpha has not gained or lost, making it appear as if his interests are aligned. But taken in total, Company A’s standalone shareholders have $6 at stake. Shareholder Alpha receives the premium and the opportunity to keep future profits.

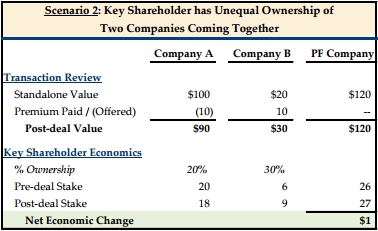

Now let’s say Shareholder Alpha owns more of the seller than the buyer. The benefit of overlapping ownership becomes more pronounced. In the example shown in the chart labeled “Scenario 2,” Shareholder Alpha owns a 30% stake in Company B and 20% in A. His shares are worth $26 before the deal, $20 from A and $6 from B but $27 after, $18 from Company A and $9 from Company B. Now Alpha’s stake is greater following the merger, and he still benefits from future appreciation. Company A could overpay for Company B, and he comes out ahead.

These examples are simplified in at least one way that matters. In most deals, including Tesla’s deal to buy SolarCity, the acquiring company often says it will be able to find “synergies”, or that the merger of A and B will produce a numeric value greater than their sum. But in the same way Shareholder Alpha gains more of the premium than other shareholders of Company A, he also receives a disproportionate benefit of the synergies, making his stake increase more as synergies are factored into the equation.

This dynamic of overlapping shareholders exists in most deals because large institutions like Fidelity own stakes in multiple companies in a single sector that merge. But Fidelity is a mere investor who does not have the same influence as a manager like Musk. The overlap becomes an issue only when those constructing a deal also have interests that diverge from the shareholders they are meant to be protecting.

The presence of the conflict in the Tesla deal has been addressed in some ways. Musk recused himself from negotiations and from voting on the deal. In the event a superior proposal emerged, Musk agreed to vote his stake in proportion to the company’s other shareholders.

However, he is behind the idea to tie the companies together. The lack of clarity around his overlapping stakes makes it difficult for shareholders to quantify the extent of the benefits to him. Also, timing matters, and Musk had something to do with this. While he didn’t discuss the exchange ratio, the timing of his general proposal to merge the companies inked the exchange ratio to the band the stock traded within a few months. Finally, his presence as a large owner and manager of both companies is a deterrent to other bidders, making it hard for shareholders to determine a true market clearing price for SolarCity.

Redstone has a similar dynamic with CBS and Viacom. His controlled entity National Amusements owns a 10% stake in Viacom and an 8.6% stake in CBS. His shares carry super voting rights, and through National Amusements which he owns with family, he maintains effective management control.

The companies have an opportunity to address these shareholder concerns if they announce a merger. There are two potential remedies. First, advisors can help assuage concerns about diverging incentives by encouraging insiders such as Musk and Redstone to disclose more than is required by offering a full picture of the financial construct of the shares, both before and after a deal.

Second, if a deal is disproportionately enriching the insider, it isn’t unprecedented for shareholders of the same company to receive different considerations. In 2009, Sprint Nextel bought Virgin Mobile. (Foros founder and CEO Jean Manas advised on this deal). The parent company of Virgin Mobile, Virgin Group, had a tax consideration that benefitted Virgin Group only. It was a wrinkle in an otherwise warranted deal. As a result, Virgin Group accepted a lower exchange ratio than other Virgin Mobile shareholders. This situation and the remedy aren’t analogous to the example above, but they are illustrative.

Ultimately Musk may succeed in closing his deal. But with more than a half dozen lawsuits afoot, Musk may be answering questions for some time to come. Redstone would do well to let him be a lone wolf.