In 2016, around 70 publicly-traded companies went bankrupt, wiping out over $3 billion of equity value in the process. Small wonder why: the impact technology is having on companies is changing not only consumer and business habits, but annihilating entire industries too.

Many companies are aware of the challenges that technology forces onto their business, and they are trying to ramp up investment efforts to keep pace. After all, their equity holders could take steep haircuts in the not too far future if they don’t adapt and consequently have to sell at a low price or liquidate. Company managers often go to great lengths to be sure a company can continue in one form or another. Consider Westinghouse, which in the late 1990s changed wholesale from an electricity company to a media one (now known as CBS), or IBM, which has gone from a maker of weighing scales, typewriters, automatic meat slicers, and coffee grinders to become a producer of software, servers, and technology services. Netflix put its main and first DVD-by-mail division out of business in order to become a leader in streaming video. All these changes took considerable risk and capital.

Then there are those who spent the money and it didn’t work out, and eventually had to be shut down, such as Nokia, Blockbuster, or Palm Inc.

In some cases, the wind down of a company may be inevitable. But what if the “close up shop” scenario became a matter of choice?

It’s not an easy concept to digest; however if timed right, shareholders might actually benefit more if the company winds itself down than if it carries on.

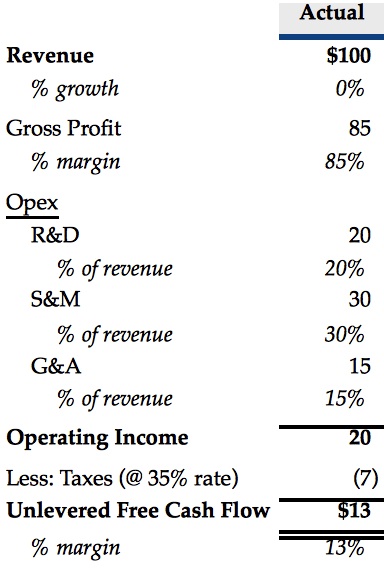

Let’s take a hypothetical software company. It has $100mm of revenue with flat growth and 20% operating margins.

The graphic above provides a rough financial outline of the company. The company is currently facing challenges. Newer businesses, such as Amazon Web Services and Splunk, are utilizing the Internet to reach a broader base of customers without needing to spend as much on bulky enterprise salesforces (a threat detailed in a Prior Foros Perspective). This dynamic has enabled the newer companies to squeeze margins out of the industry overall. The company decides it needs to spend to change, and fast.

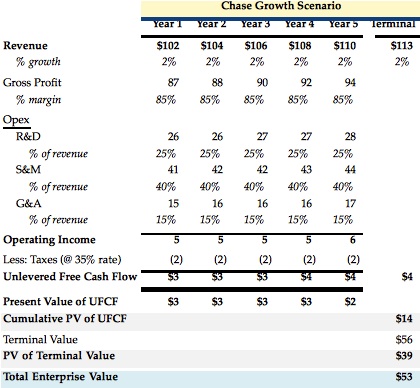

The company could boost its research and development and sales and marketing spending to fuel new products or enhance existing ones and attract new customers. The illustration below shows how it might do this – pursue growth to sustain itself.

The company boosts its research and development expense ratio by 5% and its sales and marketing expense ratio by 10%, and maintains its overhead costs at 15% of revenue. Let’s assume it achieves moderate success and is able to reach consistent 2% revenue growth as a result of these investments, despite the declines in its legacy product lines.

If we assume that in perpetuity the company grows at 2%, roughly in line with inflation, using an 8.5% discount rate ¹, the company would have a net present value of $53mm.

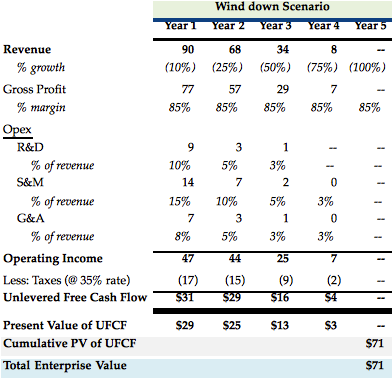

Now let’s take a look at the company if it decided to turn off the spending machine and wind down. It cuts its R&D expense ratio in half in the first year, and completely eliminates R&D by year four. The S&M expense ratio is cut in half in year one and then gradually reduced in subsequent years to maintain remaining customer relationships. It proportionally trims G&A to keep things running smoothly and oversee the wind down.

Many customers will ultimately leave and the pace of the company’s decline will increase. However, for customers that have software embedded into their company’s operations, systems, and processes, some will only gradually seek replacements and may continue to use the product for some time. The corporation will cease to exist in a couple of years so there is no terminal value, but the value of the cash flows in the first couple of years is $71, which is roughly 33% greater than in our scenario in which the company decided to invest to grow.

Winding a company down may seem like an interesting theory but highly impractical. However, it is not without precedent. Foros advised a mobile virtual network operator (“MVNO”) and invoked the alternative of a wind down during sale negotiations. MVNOs essentially lease wireless network infrastructure, such as base stations and transceivers, from major network operators (e.g. AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and T-Mobile) and sell these services to consumers. MVNOs incur significant customer acquisition costs, namely marketing and handset subsidies, to increase their subscriber base.

Once an MVNO develops a sizable customer base, suspending all promotional spending is a highly profitable endeavor in the near-term given the stickiness of its customer base. In the midst of a highly competitive landscape, this MVNO concluded that opting to harvest its existing subscribers would prove more valuable to shareholders than plowing in investment dollars to sustain moderate top-line growth. While not effectuated, this analysis demonstrated that the potential shareholder value of a wind down was far superior to the public trading value, which had the embedded assumption of continued investment to chase growth. The ultimate sale of the MVNO was at a premium to the wind down value and therefore a substantial premium to market value.

Of course, there is risk embedded in both scenarios. In the first, “chase growth” scenario, it could be a fairly generous assumption that the company will grow revenue in perpetuity, in the face of steadily declines in its larger legacy businesses. Once a company’s growth slows, it can become harder to attract talent and it becomes more challenging to keep up with the rapidly changing technology and business landscape.

In the wind down scenario, stakeholders have risk too. For example, customers and employees could leave for a competitor more quickly than expected if they sense that the company is winding itself down.

Even when adjusted for risks, however, there are cases in which a graceful wind-down of a business could create more value for shareholders than investing in growth opportunities with a low return on invested capital.

¹ The 8.5% cost of capital is calculated using a 2.8% risk-free rate based on the 1-month average U.S. 20-year treasury yield as of 03/28/17, a 6.1% market risk premium per Ibbotson and levered beta for the S&P 500 of 1.0; in calculating after tax cost of debt, we use a pre-tax cost of debt of 4.0% based on the 1-year average 5-year U.S. corporate BBB effective bond yield and a 35% tax rate; we assume 10% debt to total capitalization ratio, which is the average ratio for US public tech companies per FactSet.